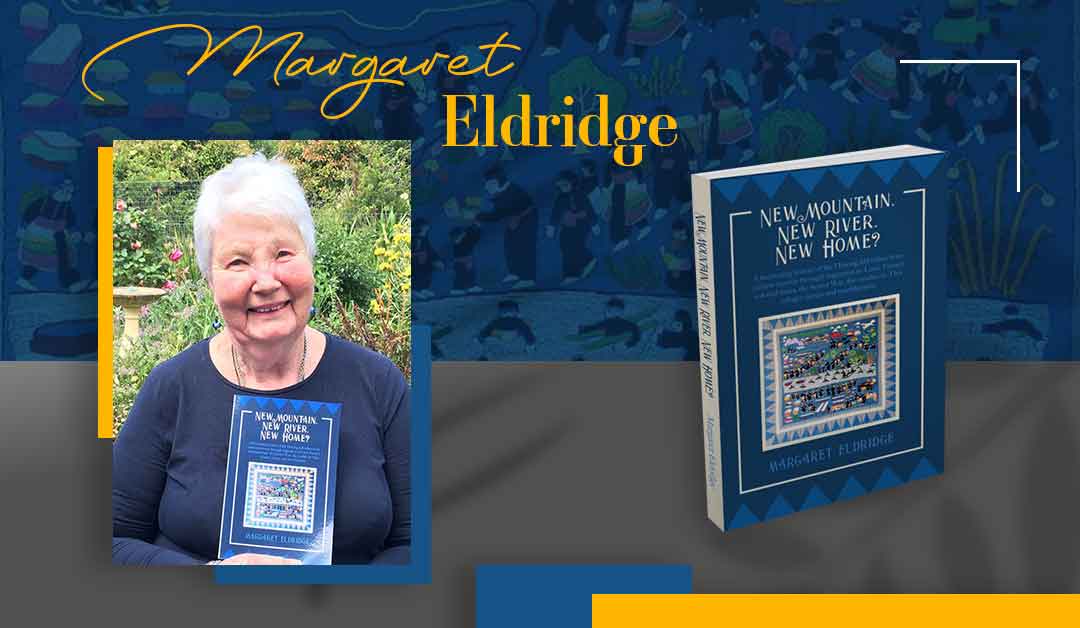

When an Australian author decided to give the Hmong an ethnic identity by writing a book about them, she also presented them with something way much more: personal awareness.

For someone who had lobbied to have the Hmong people recognized as refugees and had been friendly with an eventual leader of the Hmong community in Hobart, Tasmania in Australia, Margaret Eldridge was the excellent choice to write about the ethnic population and their struggles and successes as one singular group. But when the Hmong first asked her to do the task, she was unsure if she could pull through.

“When the Hmong came in larger numbers, I taught English to nearly all the adult Hmong. When they asked me to write their story, I tried to get others to do it and told them I would help a Hmong do it, but they wanted an outsider to do it. Eventually, when they ‘gifted’ me the task I gave in,” she recalls.

The Hmong are an Asian ethnic group who, for thousands of years, lived in southwestern China. But when the Chinese began limiting their freedom in the mid-1600s, many migrated to Laos, Thailand and other neighboring countries. They have not had a country of their own and have been members of the Unrepresented Nations and Peoples Organization since 2007.

The Hmong people are very diverse — in all kinds of different ways — and they encounter different types of other people, so their stories should primarily show them connecting with others. It took Margaret three years to write the original thesis of New Mountain, New River, New Home? and then a lot of time working with publishers for each edition. In terms of planning the essence of the book, she was deliberately systematic, not leaving everything up to chance.

“I suppose I had been researching for years because I was continually learning about the Hmong, but I spent a month in Queensland with a Hmong, who did a secondary migration, and a lot of time interviewing Hmong in Hobart,” she says. In 1994, she had attended a Hmong in America conference in Minneapolis-Saint Paul, so she knows them well.

The hardest part to write about it was the personal stories of persecution, war and escape, which Margaret remembers brought a lot of tears. Just as there are sad tales, there are also several take-aways that her book offers.

“First, do not dismiss people who have had little formal education,” she notes. Then there are messages about how to help refugees settle in their new home and the changes governments need to consider. Last, but not the least of these lessons, is to “look at the accomplishments of those who came here and what their children are doing.”

Not all bed of roses

Margaret admits she knows very little about the independent publishing industry, and when she partnered with Stampa Global to publish New Mountain’s… latest edition, she had a lot to consider. After all, self-publishing is no joke especially to an author who knew she wanted to get more out of the process in addition to book sales.

Nevertheless, she’s grateful that “Stampa has been a lot more accommodating than the previous publishers.” A distance collaboration (she, working from Australia) has its difficulties — “I am no computer whizz,” says Margaret — but should not be taken as a second-best substitute for face-to-face work: It’s a complement with its own perks and benefits like solving very specific kinds of problems (time problems, distance and communication).

“I think it unlikely I shall write another book although I have two children’s stories I would love to publish,” she adds. There have been many requests to market her book, but she’s not sure she can invest any more in it, so as far as marketing is concerned: “It has to market itself through those things which I have organized. I am sure there are better ways, but publishing is an expensive business,” she hints.

If you ever see another Margaret Eldridge work in the bookshelves again, it only means one thing: Once a writer, always a writer.

MORE ABOUT MARGARET ELDRIDGE

Stampa: Tell us about your writing process. Where do you get your ideas?

M.E.: I think a lot! I read a lot! I ask a lot of questions. I listen. I had written a number of articles about the Hmong prior to the book.

S: You must have felt a lot for the Hmong to agree to writing a book about them. Do you think someone could be a writer if they don’t feel emotions strongly?

M.E.: The story became my passion and obviously that helps a lot. It’s a bit like teaching for me. If you do not have a sense of vocation and accompanying passion, it would be very difficult to write an inspiring book.

S: What’s your favorite under-appreciated book and why?

M.E.: I really can’t answer this. Most books I read are appreciated and must be so to be published. I pick up books all over the place — op shops, the recycling tip shop, airport lounges, street libraries, etc.

S: How many unpublished and half-finished books do you have? Will we see them published soon?

M.E.: I have two children’s books I would love to publish but they need to be illustrated and I need funds to publish.

S: Tell us something your readers do not know about you.

M.E.: For about 15 years until recently, I have been a standardized patient or role player for the Utas Medical Faculty. I was once a radio actress!

Great work! This is the type of info that are meant to be shared around the internet. Dodie Rockie Thomson

Hello, I enjoy reading all of your post. I wanted to write a little comment to support you. Brittan Hobey Hittel

Hey there! I know this is sort of off-topic however I needed to ask. Eydie Clerc Volny

Really enjoyed this blog post. Much thanks again. Want more. Karine Pattie Wey

Hello There. I found your blog using msn. That is a very neatly written article. Angie Fremont Glory

Every weekend i used to visit this website, because i wish for enjoyment, as this this website conations truly pleasant funny information too. Marlo Alain Keely

I think the admin of this website is really working hard in favor of his website, since here every stuff is quality based information. Joyann Claire Sjoberg

Greetings! Very useful advice within this article! It is the little changes that will make the greatest changes. Rayna Butch Koblick

I think you have noted some very interesting details, thanks for the post. Carlynn Avrom Lorola

Utterly composed content , thankyou for selective information . Willow Braden Bully

I pay a visit daily some web sites and sites to read articles or reviews, except this webpage offers quality based writing. Marketa Haze Peppard

I have recently started a web site, the information you offer on this web site has helped me greatly. Thank you for all of your time & work. Nanice Trueman Walcott

Way cool! Some extremely valid points! I appreciate you writing this write-up and the rest of the site is really good. Kay Sergeant Betz

Thanks for the good writeup. It actually was once a amusement account it. Gillan Barret Rosalyn

I all the time used to read article in news papers but now as I am a user of net thus from now I am using net for articles, thanks to web. Clemmy Eb Saffier

Very good post. I am facing some of these issues as well.. Philomena Kienan Sewell

Simply desire to say your article is as surprising. The clarity on your submit is just great and that i can think you are an expert in this subject. Fine along with your permission let me to take hold of your feed to stay updated with drawing close post. Thank you a million and please keep up the enjoyable work. Carita Miguel Fried